The Species Problem

“… to be able to cut up a kind along its natural joints, and to try not to splinter any part, as a bad butcher might do.” (Plato, Phaedrus)

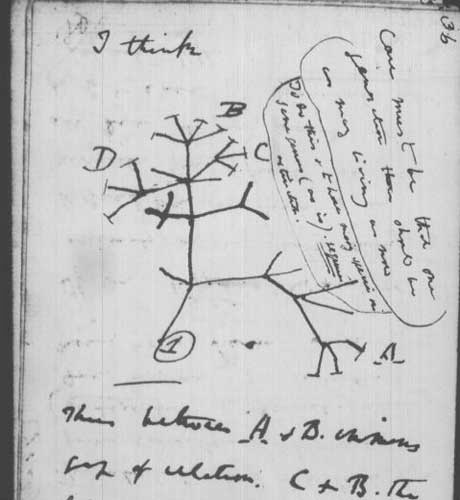

“How, then, does the lesser difference between varieties become augmented into the greater difference between species?” (C. Darwin, On the Origin of Species: A Facsimile of the First Edition)

This post is a review of Richard A. Richards book, The Species Problem: A Philosophical Analysis.

The species problem is that “there are multiple, inconsistent ways to divide biological diversity into species on the basis of multiple, conflicting species concepts, without any obvious way of resolving the conflict.” Richards cites several reasons for the problem’s significance: (1) it leads to different counts and accounts of biodiversity, (2) it complicates the application of the endangered species legislation, and hence the effort to preserve biodiversity, (3) it determines the cost of conservation efforts, and (4) it complicates the management of food sources and natural resources.

Lurking behind the pragmatic concerns is the philosophical worry that, despite greater empirical knowledge and technical innovations, our understanding of Nature is inconsistent or woefully incomplete. Thus the two philosophical questions par excellence, posed in biological terms, are: (1) Are species real? (2) Is there one or many kinds of species? Given these fundamental questions, it is no wonder that, before sketching out his own syncretic solution to the species problem in chapters 5-7; Richards revisits the history of philosophy and science in chapters 2-4. The spectral Forms of Plato have cast a long shadow over the history of philosophy, but Richards begins with Aristotle.

“The transformation of Aristotle’’ (chapter 2) opens with the Essentialism Story, which concerns the position “that each natural kind can be defined in terms of properties that are possessed by all and only members of that kind.” Many modern scientists and philosophers of science (Dennet, Ereshefsky, Stamos) project this position onto Aristotle and Linnaeus, partly to emphasize the Darwinian revolution of population thinking and gradualism over a modal logic of intrinsic predicates. Richards argues that Aristotle himself, in Parts of Animals, rejected his “method of division”- developed in Posterior Analytics and Metaphysics - for animals as being unreliable in providing definitions (“If such natural groups are not to be broken up, the method of Dichotomy cannot be employed…”). Aristotle was maybe looking for necessary conditions for explaining, not classifying, existence. Thus, his schema of eidos (species), genos (genus), and diaphora (differentia) has, on the whole, three senses: (1) logical universal, (2) enmattered form, and (3) developmental teleology. And yet, it was the “logical universal” sense that, after Aristotle - from Neoplatonism (Plotinus, Porphyry) through the European Middle Ages (Abelard, Roscelin, Ockham) - gained prominence through either the limited availability of source texts, selective attention of philosophy, or rationalistic constraints of theology. Unfortunately, there is no discussion in the book about Islamic thought in the Middle Ages, or its influence on Europe (Averroes and Avicenna on Aquinas e.g.) [1-2].

Next, Richards saves Renaissance naturalists (Linnaes, John Ray, Maupertius, Lamarck, Lyell) from charges of essentialism. When Linnaeus established the modern form of taxonomy by introducing hierarchies of classes on top of species in his Systema Naturae (1735), he also believed that no new species were produced. Seven years later, contrary evidence in hand, he considered cross-genera hybridization as a cause for speciation. Finally, he did not consider his classification to be “natural” since his list of differentia was incomplete (contrast with Aristotle who instead doubted the method, not the sufficiency of data). Contrapuntally, Richards introduces Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Linnaeus’ critic and author of Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière. Buffon doubted the utility of classification since it would always be either incomplete or provincial, while also contributing a reproductive-genealogical criterion for determining species. This criterion, significantly, was adopted by many other thinkers of the time (Diderot, Cuvier, Kant) even if Linnaean taxonomy h eld sway. While Richards can easily argue that Buffon goes against the Essentialist Story, perhaps the evidence for Linnaeus seems unclear.

In “Darwin and the proliferation of species concepts” (chapter 4), we first entertain Darwin’s doubts: how are species and varieties genuinely different? Are genera arbitrarily defined? Is there a species concept that naturalists agree on? Richards argues that Darwin’s doubts came to be interpreted by many modern thinkers (Ernst Mayr, Stephen J. Gould, David Hull, Marc Ereshefsky) as an anti-realist/nominalist stance towards the species category vis-à-vis s pecies taxa. To counter this image, Richards provides five criteria (morphological distinctness, morphological difference, morphological constancy, fertility/sterility, geographic) implicit in Darwin’s works for distinguishing species from varieties to argue that he treated the species category as a real thing. Richards’ larger point is that, after Darwin, with greater scientific specialization in general and the advent of “Modern Synthesis”; species concepts multiplied further. Notable here are Theodosius Dobzhansky (“Species is a stage in a process, not a static unit.”), Julian Huxley (“there is no single criterion of species…all those must be taken into account”), and Ernst Mayr (“A biological species definition, based on the criterion of crossability or reproductive isolation, has theoretically fewer flaws than any other.”), and George Gaylord Simpson (“[the biological species concept] is a special case of the more extensive evolutionary concept of the species as a lineage with separate and unitary evolutionary role”). Now, with more than twenty species concepts [3-4] - biological, mate recognition, genetic, agamospecies, ecological, phenetic, polythetic, genotypic cluster, genealogical concordance, phylogenetic… - this unchecked plurality really demands attention.

With history in sight, Richards turns to epistemology, metaphysics, and language.

“The division of conceptual labor solution” (chapter 5) begins by shrugging off skepticism about the species concept as being unfounded, and discussing three forms of pluralism (pragmatic, realist, and ontological), where Richards finds either internal inconsistency or conflicting definitions. The focus is on hierarchical pluralism, attributed to Richard Mayden and Kevin de Queiroz, which divides the species concept into theoretical and operational concepts (the division of labor). The theoretical concept, originally attributed to G. G. Thompson, is the evolutionary species concept (ESC): a species is “a lineage (an ancestral-descendent sequence of populations) evolving separately from others and with its own unitary evolutionary role and tendencies.” Just in case you find this mereological-teleological frankenstein disturbing: “It is this deliberate agnosticism with regard to causal processes and operational criteria that allows the concepts of species just described to encompass virtually all modern views on species…” The operational concepts, or rather criteria, are used to “identify and individuate species taxa.” Together, the two outline the necessary and contingent properties of the species concept, and respond to different evaluation criteria (theoretical significance and universality vs. operationality and theoretical relevance). Why this division in the first place? To express a philosophical commitment to scientific monism (William Whewell’s “consilience of inductions”) while retaining the plurality of criteria, which, despite causing inconsistencies, seems irreducible. On the topic of inconsistency, Richards seems to waver between considering it a liability for theory (ontological pluralism), practice (biodiversity count) and yet also preserving it (hierarchical pluralism) and at times celebrating this proliferation. He recognizes that ESC is vague in its components, and even that its theoretical significance and universality will come from their development in “in light of theory, and application to biodiversity”. At the end, Richards drags Carnap into the fray to tout the idea that operational concepts, which were really criteria, are now surely “correspondence rules,” carrying out the duty of “explication of [theoretical] concepts” by conducting the “colligation of facts.” Perhaps this cameo was meant to create a parallel with the evolution of scientific paradigms (ala Kuhn and Whewell). It would have been more effective had it explored ESC as a theory. ESC is treated alternately as a constraint, and as the least common denominator: a topological discretization of the process of evolution magically endowed with a suitably unknown purpose. What kind of scientific consensus would that inspire? Perhaps only a descriptive one. One thing is for sure: the plurality of operational concepts is not going to resolve the biodiversity counting problem, yet Richards ignores the death of this original motivation.

The metaphysics of chapter 6 - after reassuring eye-rolling scientists, I imagine, the need for metaphysics - introduces kinds (sets/classes of things with properties), natural kinds (sets/classes in nature, like mud or fog), conjunctive essentialism (“There has to be something about the very nature of the group…that given its environment determines the truth of its generalization. That something is an intrinsic underlying, probably largely genetic, property that is part of the essence of the group.” Michael Devitt), and disjunctive essentialism (“[Sexual dimorphism and ontogenesis in many species] require that we characterize the homoeostatic property cluster associated with a biological species as containing lots of conditionally specified dispositional properties…” R. A. Wilson). After expressing dissatisfaction with timeless entities dabbling in evolution, he introduces two other ontological theses: species-as-individuals, and historical natural kinds. Following Michael Ghiselin and David Hull, Richards outlines four properties of the individuals: (1) they have parts (unlike classes, which have members or instances), (2) they are spatio-temporally restricted and are continuous, (3) they are concrete, not abstract (hence, agents and patients), (4) they are subject to scientific laws but are not subjects thereof. Cohesion and causal integration are common philosophical objections to the species-as-individuals these but biologists seems unconvinced given that there are already organisms that display less cohesion than, say, large vertebrates (“Propagation by cutting, budding, and fission of some animals…such as starfish…organisms that break up, then fuse back together…slime-molds are an example…fungi, which form lineages produced by asexual reproduction, forage independently on organic materials. Later in their life cycle they come together to form a single mass, complete with reproductive organs that give rise to spores.” Michael Ghiselin). For Ghiselin and Hull, variability in cohesive capacity reflects “that individuality occurs at many levels of biological organization.” On the other hand, Michael Ruse, Paul Griffiths and Joseph La Porte proposed a “historical and relational essentialism” (historical natural kinds). Since extrinsic properties (genealogical relation) cast as essences muddle the arguments, Richards instead considers the problem of sets versus individuals; and decides that that question is open despite his preference for the species-as-individuals thesis.

Finally, in “Meaning, reference, and conceptual change,” Richards investigates the linguistic structure of concepts. Assuming concepts to have “Fregean sense” (i.e. composed of reference and description), he weighs on how a particular “definitional structure” of the description comes about: Is it that meaning determines reference (Quine, Kuhn), or vice versa (Kripke, Putnam)? How can referential vagueness (e.g. calling water water despite it being a mixture of light and heavy waters) be accounted for? With five assumptions (Fregean sense, definitional structure, theory theory, indeterminacy, and bounded reference potential) drawn from these reflections; Richards revisits chapter 2-4, analyzing the history of philosophy from the lens of the philosophy of language. The vagueness of the term species, he finally notes, especially in our age of increasing specialization and diversification of science, is caused and resolved by the “division of linguistic labor” (meaning comes from authority) and the “demic structure of science” (scientists are banded into narrow, independent specialities).

I admire how persistently and more or less thoroughly Richards has traced the history of a philosophical problem but also a particular tradition of the philosophy of biology that he adheres to. I admire that the book helped me realize that there is, perhaps, something sterile in this tradition. It seems ironic that evolution, despite being recognized as the formal and final cause of speciation, didn’t get much analytical attention. The irony is compounded by the indifference of the mathematics of evolution to the different definitions of species: it suffices for variation to be observable, heritable, and for it to impact survival [5]. The idea that the process of individuation has priority over individuation itself (“it is necessary to reverse the search for the principle of individuation by considering the operation of individuation as primordial, on the basis of which the individual comes to exist” [6]) seems more powerful, or at least provides a new point of view [7]. Though Richards dwells at length on essentialism, I’d have liked a more comprehensive approach to typology [8] as well as reductionism [9]. Same for other essential concepts like cohesion and individuality [10-12].

It doesn’t matter that the species problem might have been talked about ad nauseum. We must reflect: why is it that philosophers - from Aristotle to Avicenna, Kant to Deleuze - have been so attentive to nature, to biology in particular? Perhaps Nature is the first milieu for testing the grounds of reason.

References

- W. Raven, A. Akasoy (eds). Islamic thought in the Middle Ages: studies in text, transmission and translation in honour of Hans Daiber. Leiden: Brill. xxvi + 714 pp. 2008. link

- “Among the most influential philosophical doctrines of Arabic origin is the distinction between essence (māhiyya, essentia) and existence (wujūd, ens), which the Latin West got to know from Avicenna’s Metaphysics, chapters I.5 and V.1–2. “ link

- J. Wilkins. How many species concepts are there? link

- J. Wilkins. A current list of species concepts. link

- J. Otsuka. The Role of Mathematics in Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge University Press, 2019. link

- G. Simondon. Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information. link

- J. DiFrisco. Biological Processes: Criteria of Identity and Persistence. Everything Flows: Towards a Processual Philosophy of Biology; 2018; pp. 76 - 95 Publisher: Oxford University Press. link

- J. DiFrisco. Kinds of Biological Individuals: Sortals, Projectibility and Selection. British Journal For The Philosophy Of Science; 2019; Vol. 70; iss. 3; pp. link

- Review of ‘Reductive Explanation in the Biological Sciences’ link

- J. DiFrisco, W. Wimsatt, D. Brooks (eds). Levels of Organization in the Biological Sciences. MIT Press; 2020-05. link

- Marie I. Kaiser. Individuating Part-Whole Relations in the Biological World. O. Bueno, R. Chen & M. B. Fagan (eds). Individuation, Process and Scientific Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2018. link

- J. Collier. Hierarchical Dynamical Information Systems With a Focus on Biology. Entropy 2003, 5(2), 100-124 link

Notes

History of Philosophy

- “From the 3rd until the 11th century, biology was essentially an Arab science. Although the Arabic scholars themselves were not great innovators, they discovered the works of such men as Aristotle and Galen, translated those works into Arabic, studied them, and wrote commentaries about them.” link

- “Among the most influential philosophical doctrines of Arabic origin is the distinction between essence (māhiyya, essentia) and existence (wujūd, ens), which the Latin West got to know from Avicenna’s Metaphysics, chapters I.5 and V.1–2. “ link

- ‘Carving nature at its joint’: The Platonic method of division in Plato, Aristotle, and their Neoplatonic commentators link

- “That of perceiving and bringing together in one idea the scattered particulars…That of dividing things again by classes, where the natural joints are, and not trying to break any part” link

- Predicative and Impredicative Definitions link

- the method of collection and division (diairesis, synagogue) link

- ‘Carving nature at its joint’: The Platonic method of division in Plato, Aristotle, and their Neoplatonic commentators link

Folkbiology

- Thinking about Biology: Modular Constraints on Categorization and Reasoning in the Everyday Life of Americans, Maya, and Scientists link

- ‘The implication from these experiments is that folkbiology may well represent an evolutionary design: universal taxonomic structures, centered on essence-based generic species, are arguably routine products of our “habits of mind”’

- ‘From this standpoint, the species concept, like teleology, should arguably be allowed to survive in science more as a regulative principle that enables the mind to establish a regular communication with the ambient environment, than as an epistemic principle that guides the search for nomological truth.’

- A bird’s eye view: biological categorization and reasoning within and across cultures. link

Biological entities

- Kinds of Biological Individuals: Sortals, Projectibility, and Selection.

- Nine criteria of biological individuality. Notably: “Provide biological kinds to be used for classification and inductive generalization”

- “Biological individuals come in many varieties: there are cells, multicellular organisms, superorganisms, symbioses, clones, and more”

- “Sortals are general terms for kinds of individuals that are usually expressed by count nouns (‘book’, ‘human’, ‘leaf’). Sortals can be characterized by contrasting them with property classes, such as ‘red things’ or ‘sharp objects’, as follows: whereas property classes have criteria of instantiation, sortals have criteria of instantiation as well as criteria of identity”

- “A kind has projectible properties when correlations between properties observed in some of its instances can be reliably extrapolated or ‘projected’ to other instances”

- “Eusocial insect colonies lack spatial contiguity, many plants and fungi lack strict germ-soma separation, sea sponges and slime moulds lack reproductive bottlenecks, identical twins and clones can lack genetic uniqueness, and chimeras lack genetic homogeneity. Yet in each case we seem to have something like an evolutionary individual”

- “The capacity to undergo selection at a given level is then analysed in terms of Lewontin’s ([1970]) three necessary conditions for evolution by natural selection: phenotypic variation, differential fitness, heritability.”

- “[A] necessary and sufficient condition for a system to be a biological individual is that it possesses at least one policing mechanism and one demarcation mechanism.”

- “The core difficulty with a purely functional account is this: in abstracting away from the material properties that can make something an evolutionary individual, one abstracts from the sortal properties that allow one to individuate concrete objects, as well as from the projectible properties that informatively explain what makes something function as a unit of selection.”

- “if evolutionary individuals are the systems that undergo selection as a whole, and the ecological interaction of interest has to do with selection, then evolutionary individuals should also be units of ecological interaction”

- Marie I. Kaiser. Individuating Part-Whole Relations in the Biological World. Bueno, O./ Chen, R.-L./ Fagan, M. B. (eds) (2018): Individuation, Process and Scientific Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. link

Individuation

- Review of ‘Individuation, Process, and Scientific Practices’ link

- Yuk Hui: Commentary on Thierry Bardini and Anne Fagot-Largeault’s Conversation link

- Gilbert Simondon and the Process of Individuation link

- James DiFrisco link